First Nation Terminology

First Nation Terminology

Aboriginal peoples is a general, collective name for the original peoples of North America and their descendants.While it is sometimes used generally to refer to the indigenous peoples of the United States, this term is more often used in Canada, because while it is a general, catch all term, it also has a legal standing in Canada, and therefore is particular to the Canadian context.The term Aboriginal came into legal existence in 1982 when it was defined in section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982. Section 35(2) defines Aboriginals as including:“Indians (commonly referred to by others, depending on context, as First Nations, Status Indians, Non-Status Indians, or Treaty Indians or Non-Treaty Indians), Métis, and Inuit (also interchangeably referred to as Eskimo in common use).”These are three distinct peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.Being Aboriginal does not mean one has legal Status; Status is held only by Indians as defined in the Indian Act. We'll get into that further down in this article.Indigenous does not have the same Canadian national legal connotations. It is a general term widely used internationally. Indigenous just means a people originated in a particular area or country, and were living there before any other races migrated into the territory where they live. Indigenous can be used interchangeably with the phrases First People or Natives.

There are a number of sub-categories that apply to Status Indians. One category is Band Membership.A Band in Canada is a legally recognized “body of Indians for whose collective use and benefit lands have been set apart AND/OR money is held by the Canadian Crown, or declared to be a band for the purposes of the Indian Act.”A Band is defined as a group of Indians for whom land has been set aside (a Reserve), or who have been declared a Band by the Governor General (no Reserve). A Band might have a number of reserves, but can also have no land reserved at all. Think of a Band as the people themselves.Before Bill C-31, having Indian Status automatically gave you Band membership. Bill C-31 gave Bands the ability to stay under the Indian Act Band membership rules (automatic membership with Status) or make their own rules regarding membership.Thus you can have Status Indians who have no Band membership, just as you can have non-Status Indians who do have Band membership. Being a Status Indian is no longer a guarantee that you will be a member of a Band.Bill C-3 Indians face the same problems as Bill C-31 Indians did. Having Status does not necessarily mean they will be able to live on reserve or get Band Membership. The pros and cons of this are hotly debated.

First Nations are the various Aboriginal peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. There are currently over 630 recognized First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, with roughly half in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. The total population is nearly 700,000 First Nation people.Within Canada, “First Nations” (most often used in the plural) has come into general use, replacing the deprecated term “Indians” when referring to the indigenous peoples of the Americas. In the United States, this same unit is more commonly called a Tribe.

A reserve is the Canadian equivalent of the US indian reservation, an area of land set aside for a particular band or tribe of indigenous peoples.Related to Band membership, another sub-category is between reserve and non-reserve Indians. This does not refer to whether one actually lives on the reserve or not, but rather describes whether an Indian is affiliated with a reserve. These are people who have access to a reserve and the right to live there if they choose, but they don't neccesarily have to.Even though no historical Treaties were signed in British Columbia, there are many reserves, while in the Northwest Territories which is covered by a numbered Treaty, there are no reserves. I also pointed out above that you can have membership in a Band that doesn’t have a reserve at all.As in other situations, being a Status Indian does not guarantee you access to a reserve, and there are non-Status people who live on reserve as well.

Indian Status – An individual recognized by the federal government as being registered under the Indian Act is referred to as a Registered Indian (commonly referred to as a Status Indian). Status Indians are entitled to a wide range of programs and services offered by federal agencies and provincial governments that are not available to Non-Status Indians.Over the years, there have been many rules for deciding who is eligible for registration as an Indian under the Indian Act. Important changes were made to the Act in June 1985, when Parliament passed Bill C-31, An Act to Amend the Indian Act, to bring it in line with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and again in 2011 with the coming into force of Bill C-3: Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act.Status Indians are persons who, under the Indian Act are registered or are entitled to be registered as Indians. All registered Indians have their names on the Indian roll, which is administered by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC). Many people also still refer to this Ministry by older designations, such as INAC (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) or DIAND (Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development).

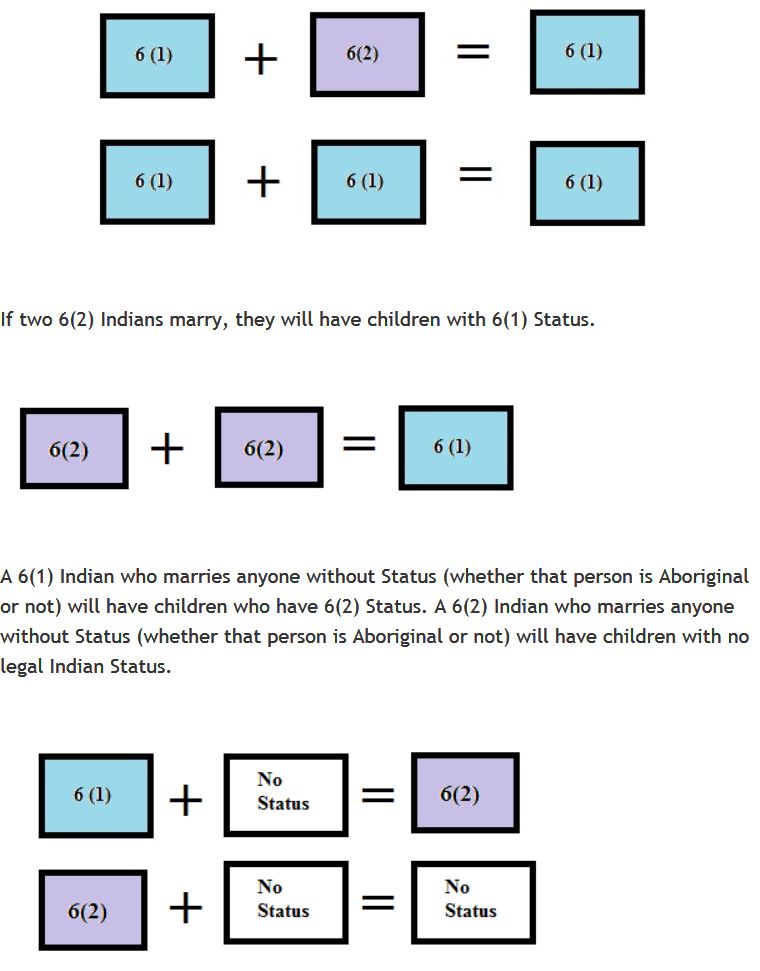

Bill C-31 amends the definition of Status. There were various federal policies over the years that caused Status Indians to be removed from the Indian roll.Some lost Status when they earned a university degree, joined the Army or the priesthood, gained fee simple title of land, or married a non-Indian (this last one applied only to women). One minute you were legally an Indian, and the next…you weren’t.Bill C-31 was passed in 1985 as an amendment to the Indian Act, and was intended to reinstate Status for those who had lost it. In particular the Bill was supposed to reverse sexual discrimination that had cause Indian women who married non-Indians to lose their Status while men who married non-Indian woman not only kept their Status, but also passed Status on to their non-Indian wives.Bill C-31 added new categories to the Indian Act, defining who is a Status Indian, and who will be a Status Indian in the future. The legislation does not specifically refer to any sort of blood quantum, therefore there is no official policy that would take into account half or quarter Indian ancestry. Nonetheless, ancestry continues to be a determining factor in who is a Status Indian.Section 6 of the Indian Act identifies two categories of Status Indians, called 6(1) and 6(2) Indians. Both categories provide full Status; there is no such thing as half Status. The categories determine whether the children of a Status Indian will have Status or not.This next bit is always confusing for people.A 6(1) Indian who marries a 6(1) or a 6(2) Indian will have 6(1) children. Everyone in this ‘equation’ is a full Status Indian themselves.

Look at this chart again. Two generations of ‘out-marriage’. That is all it takes to completely lose Status. It does not matter if you raise your grandchildren in your native culture. It does not matter if they speak your language and know your customs. If you married someone without Status, and your grandchildren have a non-Status parent, your grandchildren are not considered Indian any longer. Not legally.To be honest, it is amazing there are any Status Indians left in Canada.One of the most criticised aspects of Bill C-31 was that it did not actually reverse the sexism inherent in denying women Status if they married a non-Status man.Women who had their Indian Status reinstated under Bill C-31 had 6(1) Status, but their children had 6(2) Status. That makes sense according to the charts above, right?The problem is that men who married non-Indian women actually passed on Indian Status to their previously non-Status wives. Thus the children of those unions have 6(1) status.

Look at this chart again. Two generations of ‘out-marriage’. That is all it takes to completely lose Status. It does not matter if you raise your grandchildren in your native culture. It does not matter if they speak your language and know your customs. If you married someone without Status, and your grandchildren have a non-Status parent, your grandchildren are not considered Indian any longer. Not legally.To be honest, it is amazing there are any Status Indians left in Canada.One of the most criticised aspects of Bill C-31 was that it did not actually reverse the sexism inherent in denying women Status if they married a non-Status man.Women who had their Indian Status reinstated under Bill C-31 had 6(1) Status, but their children had 6(2) Status. That makes sense according to the charts above, right?The problem is that men who married non-Indian women actually passed on Indian Status to their previously non-Status wives. Thus the children of those unions have 6(1) status.Sharon McIvor launched an epic court battle to address the problems with Bill C-31 and the Indian Act. In response a Bill was introduced to Parliament for First Reading in March of 2010. The full title of this Bill is:An Act to promote gender equity in Indian registration by responding to the Court of Appeal for British Columbia decision in McIvor v. Canada (Registrar of Indian and Northern Affairs)Bill C-3, as this bill is commonly referred to, was given Royal Assent on December 15, 2010 and became law on January 31, 2011. A great many grandchildren of women who regained Status under Bill C-31 (but who passed on only 6(2) Status to their children) can now regain their 6(2) Status if they choose to.It is not an easy choice to make. Identity politics are incredibly convoluted and mined with danger. For others who have ‘lived’ Indian their whole lives, Status be damned, it can be an important change…but ultimately one that reinforces the so-called legitimacy of a colonial power deciding who is Indian and who is not.

Another sub-category you should know about has to do with whether or not someone is a Treaty Indian or a Non-Treaty Indian.Treaties in this context refer to formal agreements between legal Indians or their ancestors and the Federal government, usually involving land surrenders. The so called ‘numbered Treaties’ were signed between 1875 and 1921 and cover most of western and northern Canada. British Columbia, with the exception of Vancouver Island is not covered by any historical Treaty.Other Treaties were signed in eastern Canada, but there are vast areas in the east that are still not covered by any Treaty. A number of modern (since 1976) Treaties have been signed in BC, and in other areas of the country, and negotiations are still underway to create more Treaties. Some Treaties provided for reserves and others did not.There are many non-Status Indians, particularly in eastern Canada, who consider themselves Treaty Indians. In the Prairies, “Treaty Indian” is often used interchangeably with “Status Indian” although one is not always the same as the other.

Confused yet?

To sum up, Status is held only by Indians who are defined as such under the Indian Act. Inuit and Métis do not have Status, nor do non-Status Indians. There are many categories of Status Indians, but these are legal terms only, and tell us what specific rights a native person has under the legislation.If a native person is not a Status Indian, this does not mean that he or she is not legally Aboriginal. More importantly, not having Status does not mean someone is not native. Native peoples will continue to exist and flourish whether or not we are recognised legally and you can bet on the fact that terms and definitions will continue to evolve.Article Index:

Pronunciation Guide to First Nations in British ColumbiaThis chart is a guide to the pronunciation of British Columbia First Nations.Article Index:

Pronunciation Guide to First Nations in British Columbia

This chart is a guide to the pronunciation of British Columbia First Nations.

Incoming search terms:

- https://www first-nations info/pronunciation-guide-nations-british-columbia html

- bc first nations pronunciation

- first nations pronunciation guide

- first nation pronunciation guide

- how to pronounce wsanec

- bc first nation pronunciation guide

- how do i prnounce Te\mexw

- wetsuweten pronunciation

- xeni gwet’in first nation-pronunciation